In Kerala, India, a dangerous and often fatal infection caused by a brain-eating amoeba has triggered public health concern. This rare creature, Neglaria Foulry, claimed the lives of many people in the state during the festive season, highlighting the rising risks of untreated freshwater.

A recent case included a 45 -year -old woman from Malappuram, who showed mild symptoms such as dizziness and high blood pressure, but within days, her condition deteriorated. By the main day of the Onam festival, he had passed away sadly. The infection entered her system through her nose; most likely, she was exposed to untreated water sources.

The brain-eating amoeba, while extremely rare, is almost always fatal. It causes a sharp and severe brain infection known as primary amoebic meningoencephalitis (PAM). Health Authorities in Kerala are now aiming to reduce future confusion by increasing awareness campaigns, conducting preliminary testing, and issuing preventive guidelines.

What Is the Brain-Eating Amoeba?

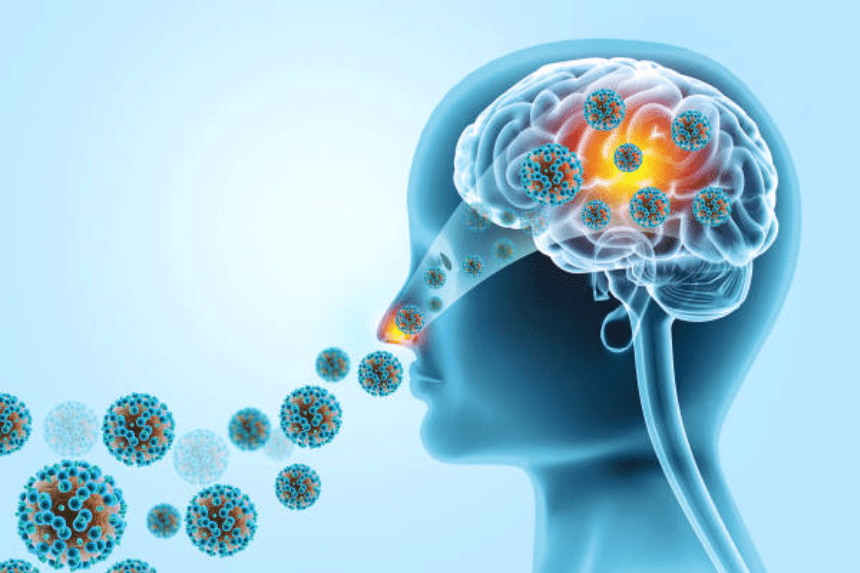

The brain-eating amoeba is a subtle, single-cell organism that thrives in lakes, ponds, rivers, and warm freshwater environments such as swimming pools. It infects people when contaminated water enters the body through the nose, especially during swimming or rinsing of the nose.

Once inside, it travels to the olfactory nerve for the brain, destroys brain tissue, and causes inflammation. The resulting position, palm, is almost always fatal. Symptoms usually begin within 1 to 9 days and include headaches, fever, nausea, a hard neck, and eventually seizures or coma. Here is the link to our article on Maternal Health Crisis.

Why Is Kerala Seeing More Cases?

Kerala has reported about 70 cases of brain-eating amoeba infection this year, with a deadly rate of about 24.5%. Although the number of infections has increased, better clinical equipment and initial treatment have improved the survival rate.

Experts believe that Kerala’s heavy dependence on groundwater and natural water bodies plays a major role. With over 5.5 million wells and 55,000 ponds, many citizens depend on these water sources daily – making them unsafe, especially when the water is untreated or polluted.

Some infections have also been detected through unusual practices, such as the use of steam. This outlines the important need for awareness about water security.

How Are Health Authorities Responding?

The Kerala government has implemented an awareness campaign and strict security measures. In one initiative, more than 2.7 million wells were chlorinated. Public advice now warns against unprotected water activities near ponds and pools. Residents are urged to use boiled or chlorinated water for nasal rinsing, avoid swimming in untreated water, supervise children, and wear nose clips while swimming. Although total prevention is difficult, better hygiene and initial identity are important. Here is the link to our article on Health Worker Backlash.

Is Climate Change a Contributing Factor?

Yes, climate change is considered an increase in risk. Rising temperatures and prolonged summer create ideal conditions for amoeba. Warmer water also supports the development of bacteria, which the amoeba feeds on.

Even an increase of 1 °C in the average temperature can significantly increase the activity of microorganisms, especially in a tropical climate like Kerala. This means that once a rare danger was becoming more normal, and potentially global.

What Treatments Are Available?

Currently, treatment involves a combination of antimicrobial and steroids. However, Medical Professionals Acknowledge That The available Drug Regimens are not optimal. The remaining people are rare, and in many cases, the diagnosis is too late to be effective for treatment.

New clinical capabilities in Kerala’s public health laboratories are helping to identify rapid infections. Nevertheless, more research is required to develop effective and targeted treatments.

Final Thoughts

The increase in brain-eating amoeba infections in Kerala reflects a major global health challenge. As climate change changes environmental conditions, rare pathogens are gaining land. Public awareness, initial detection, and responsible water practices are important for saving lives and preventing future outbreaks. The active approach of Kerala offers lessons for the same ecological and other areas facing health risks.