More than 1,000 schoolchildren across Indonesia fell ill this week after eating free lunches provided under a national programme. Official data show that 1,258 cases occurred between Monday and Wednesday in West Java’s Cipongkor area. This incident follows a prior outbreak affecting 800 students in provinces including West Java and Central Sulawesi.

President Prabowo Subianto had promoted the free meal initiative intended to feed 80 million students as a core part of his agenda. But repeated food poisoning cases have pushed civil society groups to demand a pause for safety reviews. The government insists it will continue the programme while assessing corrective measures.

What symptoms did victims report?

Children affected complained of stomach pain, dizziness, nausea, and, in some cases, breathing difficulties, symptoms atypical of ordinary food poisoning. These unusual findings have amplified concerns over food handling processes and oversight in the meal scheme. Here is the link to our article on AI Education.

What meals were served, and what might have caused poisoning?

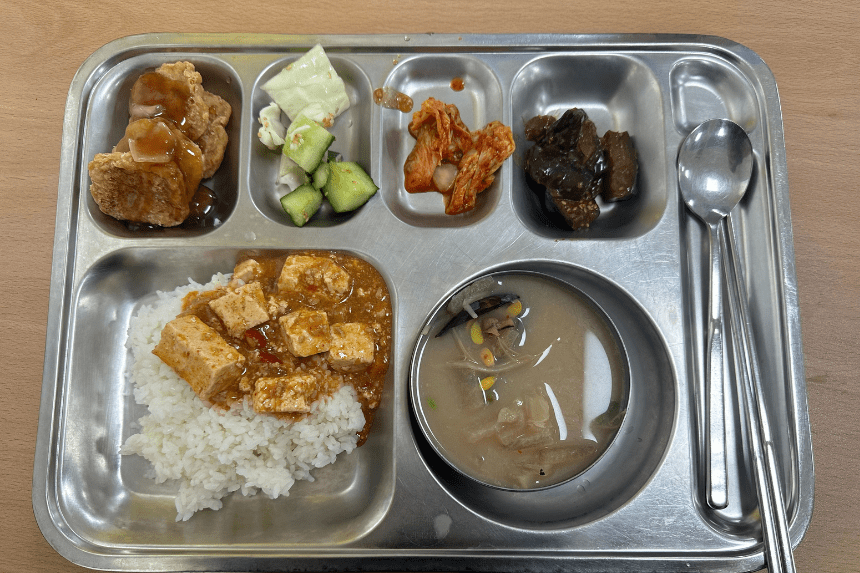

The meals distributed included soy sauce chicken, tofu, vegetables, and fruit. In earlier outbreaks, expired sauces or risky ingredients—like fried shark—were implicated. Local nutrition authorities say in the Cipongkor cases, a technical malfunction by the Nutrition Fulfillment Service Unit (SPPG) is under investigation.

How has the government responded?

Indonesia’s National Nutrition Agency (BGN) temporarily suspended SPPG operations in the affected region. Meanwhile, provincial authorities in West Bandung declared the event “extraordinary” to enable more rapid coordination and resource allocation.

The national Education Monitoring Network (JPPI) reported higher figures—6,452 affected children as of September 21—underscoring concerns over data transparency and scale. Here is the link to our article on Education cuts.

Should the programme be suspended?

Advocacy groups demand an immediate halt until an independent environmental health study clears the programme. Some propose redirecting funds to parents so they can prepare meals at home rather than relying on centralized kitchens. The BGN has rejected these alternatives so far.

Meanwhile, the cost of Indonesia’s free meal scheme—budgeted at over $10 billion this year draws comparisons to equivalent programmes in India and Brazil. Critics warn that large-scale aid programmes in Indonesia historically attract corruption risks.

What does this mean politically?

Prabowo made this food programme a central campaign pledge. He publicly defends it, citing economic challenges and competition for investment. Yet, the Indonesian school lunch poisoning incidents may erode public trust in his administration’s capacity to deliver large social programs safely.

Final Thoughts

The Indonesian school lunch poisoning crisis reveals that ambition must be matched by rigorous safety protocols. While the intended goal remains noble—tackling malnutrition and undernutrition—repeated food safety failures threaten program credibility. Unless urgent reforms are made to ensure health standards and transparency, public confidence and child welfare may both suffer.