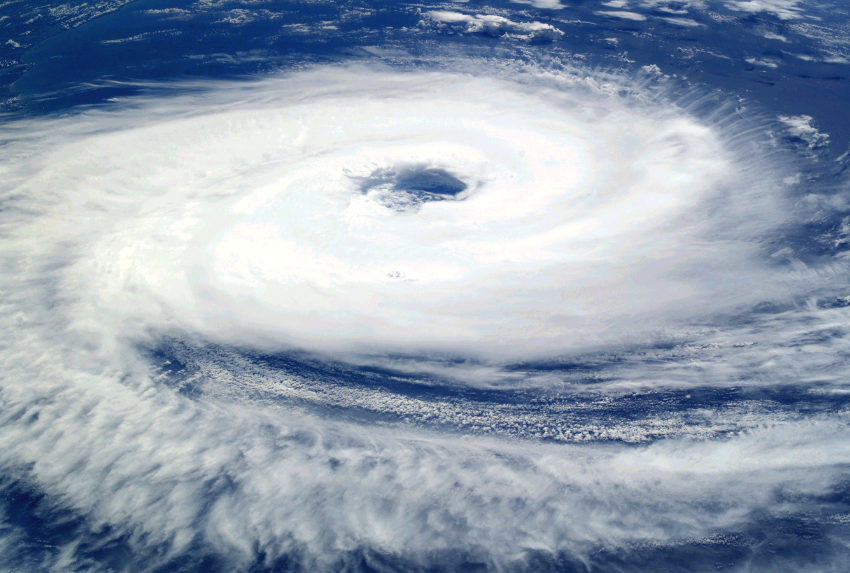

Apart from causing extensive damage, Cyclone Alfred also disrupted Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s Australian Election preparations when it tore across the east coast earlier this month.

With an eye toward rare positive economic news—a reduction in inflation and an increase in wages—Albanese had been ready to declare an April Australian Election. However, one Labor Minister said that the choice was stolen from him by “an act of God.” The Prime Minister had to pay more attention to disaster relief than to guaranteeing a second term.

Albanese had to shift from his political goal to handling emergencies, not once but rather several times. Natural disasters, economic uncertainty, and geopolitical concerns have all tried his government; each has the power to eclipse his policies and political aspirations.

Has Labor fulfilled its pledges?

Notwithstanding the challenges, Albanese maintains his government has negotiated challenging global conditions and produced outcomes. Emphasizing his party’s economic management, he remarked, “Landing where we have is like landing a 747 [jet] on a helicopter pad.”

But his first term has been full of difficulties: a cost-of-living crisis, international conflicts, economic uncertainty, post-pandemic hardships, and growing political polarities. After nine years of cautious leadership, his 2022 triumph was supposed to signal a new beginning. Key goals were climate action, cost-of-living alleviation, and stable leadership; nevertheless, his defining legacy was meant to be Indigenous matters.

As evidence of its success, the government has cited decreased inflation, pay increases, and higher employment rates. Critics counter that many Australians, who continue to battle rising mortgage and rent, have not found improved financial stability from these economic markers.

How did the Indigenous Voice Referendum go?

The referendum on Indigenous Voice to Parliament was a key project of the Albanese government. Believing this would formally acknowledge First Nations people in the Constitution, the Prime Minister campaigned fervently for a “Yes” vote.

The plan was clearly turned down, though, which demoralized many Indigenous people and left Albanese politicians wounded. Critics contend that misunderstanding and false information helped to get the result. Opposition leader Peter Dutton aggressively advocated a “No” vote, criticizing the government for giving the referendum top priority instead of attending to the cost-of-living issue.

” [Dutton] not only won on the referendum but also won on positioning Labor as the government that’s not completely focused on the issues that matter to Australia,” political consultant Kos Samaras said.

For Albanese, the lost referendum was a personal blow rather than only a political one. He had expected it would be a historic occasion of harmony and atonement. Rather, the split it caused highlighted the difficulties of the modern Australian government.

Why are people losing faith in conventional candidates?

Interest rates have risen twelve times under Albanese’s leadership (with one cut in February), inflation has skyrocketed, and the housing problem has gotten worse. Although he links many of these problems to the past Coalition administration, voters are more focused on who is most suited to address them now.

Although many Australians find Labor unsatisfactory, this unhappiness does not always translate into support for Dutton’s Coalition. Rather, endorsement of tiny parties and independents is rising. Independent candidates could balance the power if no major party gains the 76 seats required for a majority, therefore producing a hung Australian Parliament.

Other democracies also observe a tendency for independents and minor parties to emerge. Many voters investigate alternatives since they believe that conventional parties no longer reflect their interests. This change might reshape Australian politics in the next few years.

Australia’s Resistance to Political Extremes?

Disillusioned people are looking for drastic answers all around, endangering democratic stability. However, Australia’s voting system has essentially kept it free from the severe political swings observed in Germany, France, and the United States.

One main stabilizer is required voting. Nearly 90% of Australians vote in the 2022 election—far more than the 69% average among OECD nations. Since turnout is mandatory, political parties concentrate more on persuading undecided voters than on merely organizing their base.

Australia’s preferential voting method also helps to moderate polarization. Voters rank candidates in order of preference; hence, major parties have to appeal outside of their base to get second and third choices. This softens policy stances and deters radicalism.

Election expert Antony Green says, “Australia’s elections are decided in the middle. This involves getting your point of view over to those who are not particularly attentive.

These elements support Australian political stability even as voter discontent rises. However, the growing dispersion of the voters means that both big parties have more work ahead to get general support.

Might world politics affect the result of the election?

Australia’s election will be fought on home concerns, but international considerations cannot be discounted.

A few observers projected that a Trump administration would have a major effect on Australia a year ago. But the scene of world politics has changed drastically in just five months. Australians are growing worried about their nation’s position in the world, given Trump’s attitude to alliances and trade battles.

Dutton contends he would be more suited than Albanese to handle US relations headed by Trump. Still, there are questions about whether any Australian government can adequately get ready for the erratic nature of a prospective Trump presidency.

Apart from the US, Australia has to negotiate its connection with China, its main trading partner. Australia’s foreign policy will be shaped in part by trade conflicts, security worries, and geopolitical maneuvering. The Australian election winner will have to keep a diplomatic balance in a world that is becoming more and more unstable.

Who will guide Australia for the next three years?

Australians have little over a month of fervent campaigning ahead, with the Australian Election planned for May.

Albanese’s approval ratings have risen as a result of the government’s reaction to Cyclone Alfred, the highest in 18 months. Recent polls, however, indicate that Dutton’s Coalition is still a formidable competitor, so the race is rather close.

Should Albanese lose, his government will be the first in almost a century to fall short of obtaining a second term. Australia’s political future is more unknown than ever as discontent rises and support for independence increases.

Both main parties will have to answer the issues of common Australians as the campaign gets hot: growing living expenses, economic stability, and national security. The result of the Australian Election might define the direction of the country for years to come, therefore deciding not just the next Prime Minister but also the fate of Australian democracy itself.